Implementing AlphaZero from Scratch for Gomoku

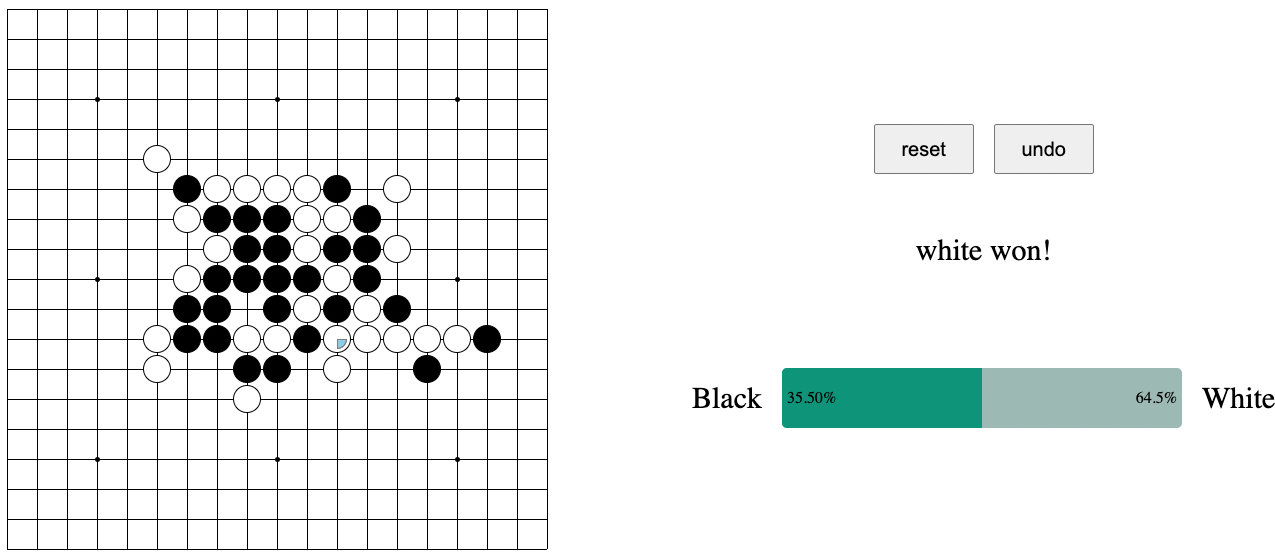

This project uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to construct an AI for Gomoku on a 19x19 board. The complete implementation is available on GitHub.

For board games, we can imagine the human player standing at the root of the tree, where its children nodes represent all possible moves the next player (AI) can make. We expand the tree recursively until we reach a terminal state (someone has won). The problem with this approach is that the tree grows exponentially, making it impossible to explore all possibilities on a 19x19 board.

Tree Search Algorithms

1. Minimax

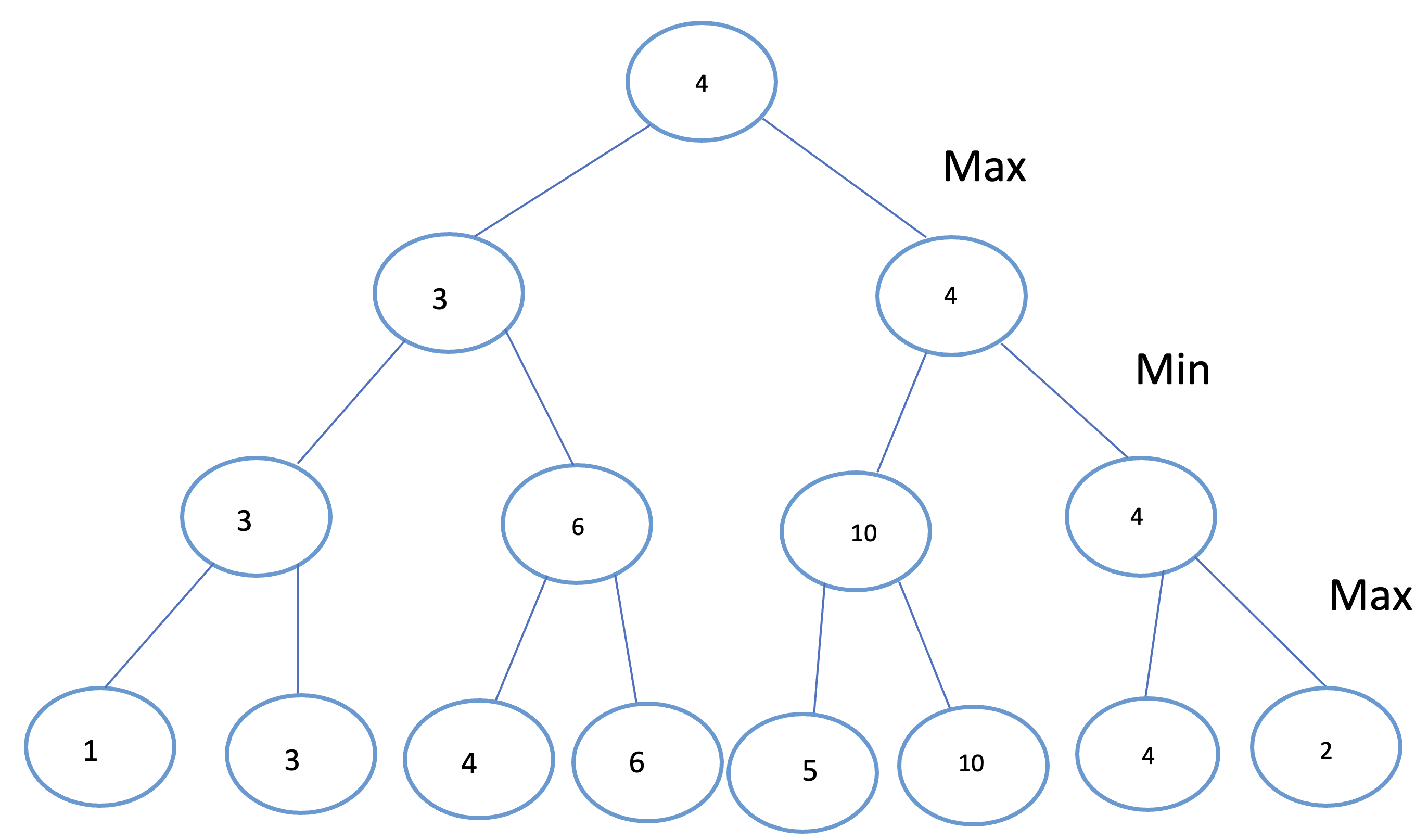

Minimax improves upon brute-force tree search by introducing a value function and a maximum depth. When the search tree reaches the max depth, the value function evaluates the state of the board at the leaf nodes. The evaluation result is backpropagated to the root of the tree by alternating between choosing the max or min of all child nodes.

For example, suppose the max depth is 3, and we are standing at the root node ready to move down the tree:

- A higher value from the value network indicates a better state for the AI player. At the root, we choose the child with the max value.

- At depth 1, it is the opponent’s turn, and they will minimize the value for the AI player.

- This alternating max/min process continues until reaching the leaf nodes.

Eventually, we choose the move represented by the child node with the highest value at the root (e.g., 4 > 3).

Limitation:

Minimax requires a value function, which is often difficult to define. This challenge leads to the use of MCTS.

2. Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

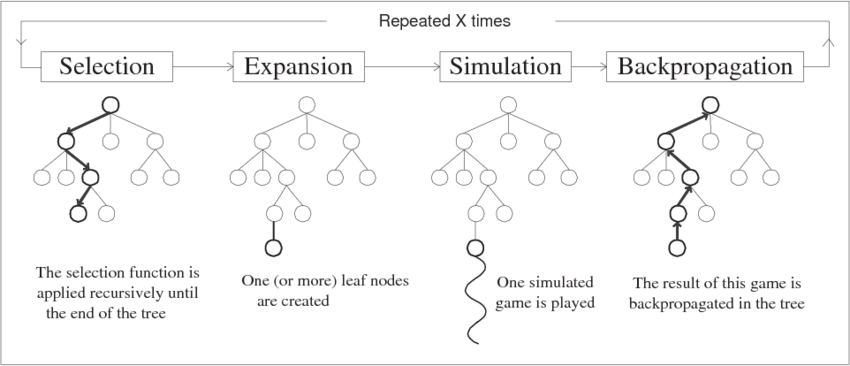

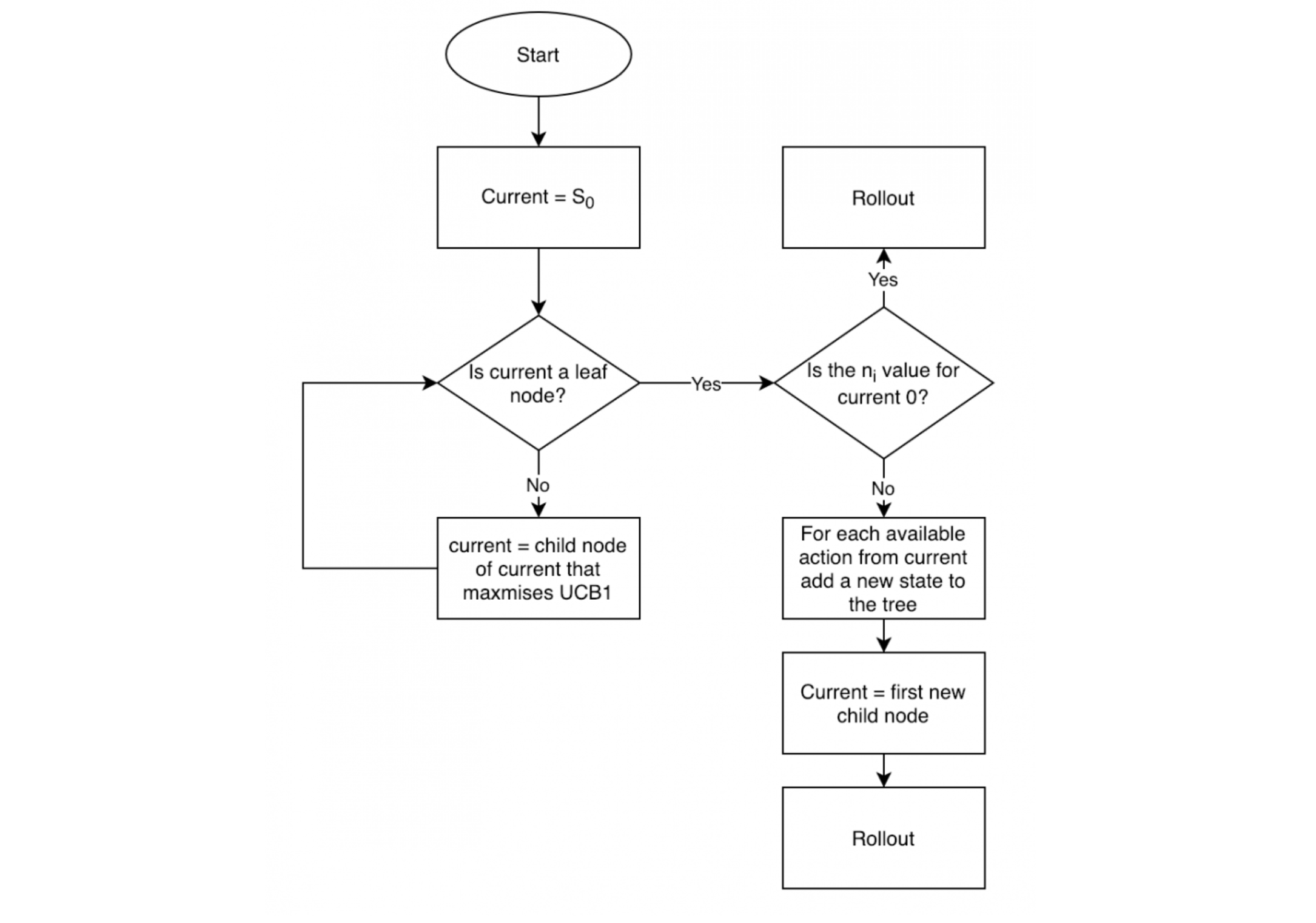

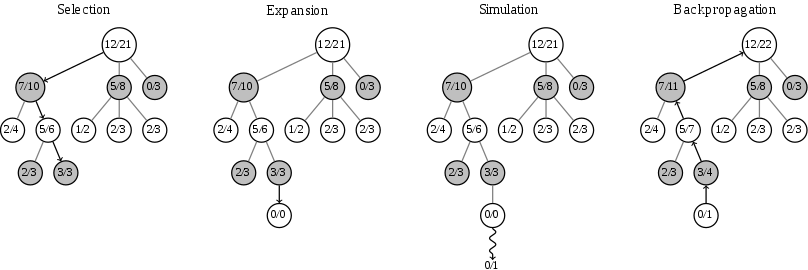

MCTS addresses the shortcomings of Minimax by removing the need for a value function. It has four main steps:

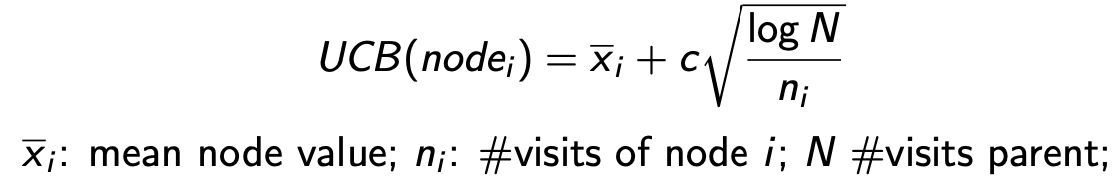

During the selection phase, we move toward the child node with the highest Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) value, calculated as:

- The mean node value is the number of AI wins divided by the number of visits to the node.

The simulation phase (rollout) randomly places stones on the board until someone wins.

After enough iterations, we choose the move represented by the child node of the root with the most visits (highest denominator). MCTS converges to the optimal solution as the number of iterations increases.

Simulation Example

Here’s an example of how value updates work during simulation:

Challenges During Implementation

Problem 1: Limited Computational Power

MCTS does not perform well on a 19x19 board when considering all possible moves during the expansion phase. For example:

- If MCTS runs for 50,000 iterations and there are 360 possible moves after Black’s first move, each move is simulated just over 100 times on average, which is insufficient.

Solution

Based on Gomoku’s rules, I assumed the best move would always be near existing stones. During the expansion phase, I limited possible actions to moves that share the same block with an existing stone. This assumption greatly improved predictions without losing much generality.

Problem 2: Rollout Randomness

The simulation stage introduced too much randomness, causing the AI to prioritize forming its own live 3 over blocking the opponent’s live 3. For example:

- When Black has a live 3 and White only has a live 2, White should block Black’s live 3. However, the AI often places a stone to form its own live 3 instead.

Solution

I implemented functions to check for live 3 and consecutive 4 formations to ensure appropriate moves are chosen. Additionally, I referred to the AlphaGo paper, which trains a fast policy network for the rollout phase, limiting randomness and improving performance.

Features

- A blue quarter-circle indicates the last move.

- A bar on the right displays the winning percentage for both players based on simulations.

- A reset button resets the board to the initial state.

- An undo button removes the last human move and the subsequent AI move.